Why the World Bank's finding of declining inequality in India is ludicrous

Ordinary consumer goods do not sell and everything from cars and homes to detergent and clothes, is going premium, and the stock market is minting billionaires and millionaires

The World Bank got it wrong when it said inequality is falling in India

If you thought fairytales were all written long, long ago, and spoke of princes and princesses, witches and evil stepmothers, and ended with the main characters living happily ever after, here is the World Bank with a modern fairytale to remove such misapprehension. No, it does not have flying carpets or many-headed monsters. Its main characters are inequality, and the gap between the rich and the poor nations, in terms of per capita income. The fictional entertainment for credulous children contained in this report relates to its assertion that India is the world’s fourth least unequal country.

The government and its supporters have pounced on the bit of geekery underlying the thesis that India has reduced inequality significantly, and tom-tommed it as a great achievement. “India’s consumption-based Gini index improved from 28.8 in 2011-12 to 25.5 in 2022-23,” says the World Bank’s Poverty & Equity Brief. It, however, qualified this statement with the following: “inequality may be underestimated due to data limitations. In contrast, the World Inequality Database shows income inequality rising from a Gini of 52 in 2004 to 62 in 2023.”

Even before the qualification, the fact that what is being referred to is inequality based on consumption, rather than income, gives the game away. Consumption-based inequality is naturally lower than income-based inequality.

Mukesh Ambani can afford to eat Japanese strawberries individually wrapped and sold in New York for $19 apiece. Even so, how many can he eat, even if he were inclined to splurge on fancy fruit? The really rich even eschew ostentatious consumption. The rich save a whole lot more than the poor.

But this is not the primary reason why consumption inequality in India looks so low. This is because India’s consumption surveys totally suck at capturing the expenditure of the rich. This had been extensively commented on when the Monthly Per Capita Consumption Expenditure (MPCE) data for 2022-23 was released (for example, My column), but is worth reiterating.

The methodology for holding these surveys has changed, in terms of the questionnaire and the period for which you ask people to recall what they consumed during the period, as well as the selection of the towns and villages where the surveys are held. If you choose villages that are close to towns, the recorded consumption would be higher than if the village chosen were a jungle hamlet in Chhattisgarh. This affects fair comparison of consumption across time.

Let us take the 2022-23 survey findings. It reported the per capita monthly consumption expenditure of the richest 5% of the population to be Rs 20,824 in urban areas. Are we supposed to take this number for real? That would be the bill for one meal at a restaurant, if four members of India’s richest 5% get together for a light repast at a restaurant that serves imported wine.

How many destination weddings, foreign holidays, designer clothes, and other instagrammable life events would be covered by that annual expenditure figure of a shade under Rs 2.5 lakh?

It is not just the highest five percent of society that under-report their consumption to those who come with survey questions on how much they consume. Rs 7,673 is the reported per capita consumption expenditure of those in the fractile class 70-80%. That means a monthly consumption expenditure figure of Rs 30,692 for a family of four in urban areas. Wouldn’t a driver, together with his wife who works as household help, earn Rs 40,000 a month in the National Capital Region or Mumbai? Are they really among India’s top 30% of consumers?

It is obvious, even without looking at statistics, that the Monthly Per Capita Consumption Expenditure figures put out by the government mislead. Now, let us look at the numbers put out by the National Statistical Office on national income. These numbers show the private final consumption expenditure, besides GDP.

If we multiply the average monthly per capita consumption for rural areas with the total rural population and the average monthly per capita consumption for urban areas with the total urban population, and add these two numbers together, we should get the total final consumption expenditure – less, of course, the consumption of those in jail, the armed forces serving at the borders, vagrants, etc. Multiply that by 12, and we should get the annual final consumption expenditure. But we do not. The per capita consumption expenditure numbers captured by surveys add up to just 49% of the consumption expenditure reported in the national income accounts.

The bulk of the missing consumption expenditure would be the expenses that the rich do not have the time or the inclination to report to surveyors who come knocking. It is because the surveys miss out on half the total consumption and a much higher proportion of the consumption of the rich that inequality measures based on consumption seem so rosy.

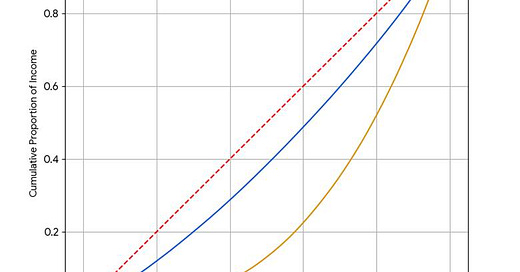

We now take a digression to ungeek the term Gini coefficient. The starting point is the Lorenz curve, named after the American economist who first proposed it. On a graph everyone is familiar with form high school, you plot the population on the X axis (the horizontal direction), and their cumulative income (or consumption or wealth) on the Y axis.

Consider a class of 50 students, to each of whom their teacher gives a toffee each. On the horizontal axis, you mark the proportion of students in the class, 1% to 100%. On the vertical axis, you mark off the proportion of toffees cumulatively handed out, 1% to 100%. In our toffee-in-the-classroom example, each 10% group of students would be 5, and each 10% batch of toffees would consist of 5 toffees. A 10% group is called a decile, a 1% group is called a percentile, and a 20% group is called a quintile, and an unspecified proportion is called a fractile.

The first 10% of students get 10% of the toffees. Draw a vertical line at the point on the X axis for 10% proportion of students, and a horizontal line at the point on the Y axis for the proportion of toffees received by the 10% students, again, 10%. The point where these lines intersect represents that particular allocation of toffees among the student population, represented as 10,10. Repeat this for the next 10%, that is, at the 20% mark on the X axis, and the 20% mark on the on the toffee axis. You get the point of intersection, 20,20. Continue till the 100% mark is reached. Now, 0% of the students get 0% of the toffees, so the point of intersection for this allocation is the point of intersection of the vertical and horizontal axes, 0,0. Join the points of intersection on the chart, and you get a straight line that extends from the point of origin (0,0), at a 45% angle to either axis. This line represents the Lorenz curve for perfectly equal allocation of toffees among the class population.

Suppose the teacher distributes toffees not equally, but to reward or penalize students for how they performed in her test. The Lorenz line would no longer be a straight line, it would curve.

On the horizontal axis, you mark off the students, dividing them into deciles (10 per cent groups) with those getting the lowest marks in the left-most decile, and the decile earning the most marks at the extreme right.. The toffee distribution you get would move below the line of perfectly equal distribution — the bottom mark-scoring decile would get less than 10% of the toffees, the bottom 20% would get less than 20% the toffees. Most students would get middling marks, so the proportion of toffees handed out would begin to rise after the second or third decile of students at the bottom, and rise sharply after the seventh decile. You will not get a smooth line if you join the points of intersection for a small sample of 50. Suppose you assume the student population to be all those taking the +2 (senior secondary) exam, you will get a smooth curve. You get the idea from the graph.

The farther the Lorenz curve moves away from the 45 degree line, the greater the degree of inequality in the distribution.

The Gini coefficient measures the gap between perfect equality and the actual distribution. It is computed as the difference between the area below the line of perfect equality and the area below the Lorenz curve, as a proportion of the area below the line of equality. If the Lorenz curve fell along the line of equality, the area below the line of equality and the area below the Lorenz curve would be same, and the difference between the two would be zero. Zero divided by anything is zero. In a perfectly equal society, the gini coefficient would be zero.

In a society in which one person got everything, the Lorenz curve would hug the horizontal axis, till it reaches the last point, where it would be a vertical straight line, and the area below the Lorenz curve would be zero. The difference between the area below the line of equality and the area below the Lorenz curve would be the totality of the area below the line of equality, and its ratio to the area below the line of equality would be 1.

Perfect equality yields a gini coefficient of 0, and perfect inequality yields a gini coefficient of 1. In the real world, the coefficient would fall somewhere between 0 and 1, the lower it is, the more equal the society.

The income inequality measured by Thomas Piketty and his team and given in the World Inequality Database might be an exaggeration. But inequality is only growing, not declining.

In India, everything is undergoing premiumization, from housing and automobiles to clothes and gourmet foods, even as mass consumption goods sales suffer, and the stock markets and tech valuations mint billionaires and millionaires on a regular basis. In this background, to suggest that inequality is falling in India is ludicrous. But they say laughter is the best medicine. Even if we don’t live happily ever after, we might live a little longer. Thanks, World Bank.

Appreciate the touch of sarcastic humour at the end of this piece. It's much needed—not only to laugh off the blatant and mind-numbing inequality, but also to help us tolerate the worsening air quality, growing political apathy, and a bleak future—except, perhaps, for the privileged few: the aristocrats, plutocrats, and bureaucrats.

Sir, wonderfully written.You may consider laughing even harder. The Indian Government wants us to live longer. PIB said we have the 4th lowest inequality by comparing consumption inequality in India and income inequality for the rest of the countries.